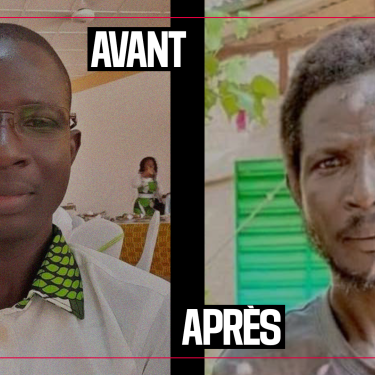

Chadian journalist describes being held arbitrarily, tortured for seven months

A journalist has endured seven months of ordeal in the maximum security prison of Koro Toro in the north of the country, more than 600 km from the capital N'Djamena. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) strongly condemns this arbitrary and abusive detention and calls on the authorities to shed full light on the most appalling violence suffered by Service Ngardjelaï.

The story of Service Ngardjelaï, a journalist with a pro-government TV channel, beggars belief. The night after thousands took part in protests against the transitional military government on 20 October 2022, Ngardjelaï was awakened by alarming noises. Soldiers stormed into his N’Djamena residence after breaking down the gate. He found himself face to face with a soldier who slapped him. Despite explaining that he was a Toumai TV journalist, Ngardjelaï was arrested and, with 15 other people, was tied up in the middle of the yard and severely beaten with sticks and whips.

Seventy-two hours of incredible violence ensued. He and the other detainees were thrown into a military vehicle “like bags” and were taken to a municipal school in Abena, a village 10 km outside the capital. While held in a classroom, he said he heard the soldiers execute several people in the courtyard, to which he was later taken and beaten. The next evening, he and other detainees were taken to an isolated place on the shores of Lake Chad by soldiers who “stubbed their cigarettes out on the bodies of the prisoners.” The soldiers were about to execute them but lowered their weapons when they saw civilians approaching.

The soldiers then took them to police headquarters in N’Djamena, where they initially promised to free them but instead set off with them heading north. Several people died from lack of food on the trip, during which the soldiers “forced the prisoners to take the bodies of the dead and throw them in the sand.” On 23 October, they finally arrived at Koro Toro, a prison in the middle of the desert, isolated from all means of communication. It is notorious for its constant gratuitous violence, which international organisations have repeatedly denounced. Ngardjelaï ended up spending seven months there.

12-kilo leg irons, deadly food

Ngardjelaï was held arbitrarily in inhuman conditions for seven months. “We slept on the floor, and there were between 20 and 30 of us in each cell,” he said. He was also subjected to forced labour. “If we refused, the soldiers attached irons weighing 12 to 16 kilos to our feet. They were so tight that they caused sores, which could then become infected.” He sustained injuries to his left ribcage, right arm, and spine, and he says he vomited blood.

He found all sorts of objects in his food, including sand, razor blades and electric battery innards. Out of date flour was used to prepare the food. He was regularly beaten by the soldiers. Some of his jailers were a little more lenient towards him before of his status as a journalist, but others used additional violence against him for the same reason.

Should never have been held

Ngardjelaï should never have spent all this time in prison. At the start of November, around ten days after his arrest, he appeared before a judicial commission consisting of a judge and a police officer and was charged with unauthorised assembly, destruction of property, arson and disturbing public order. The trial of 401 of the prisoners in Koro Toro was completed on 2 December, but Ngardjelaï was not one of them. A few days later, without his knowledge, an order was issued dismissing the case against him. The authorities had “found nothing convincing” against him. He should have been released immediately.

It was only on 7 May that Ngardjelaï was notified of this decision. That day, a commission arrived in the prison to try some of the detainees. Ngardjelaï ran into two lawyer friends, who questioned his presence in the prison as his name did not appear on their list of defendants. He told them he had appeared before a judicial commission six months earlier. The lawyers then located the December order dismissing his case. He was finally released on 12 May after a seven-month ordeal. For five months, the Chadian authorities had “omitted” to notify him of the decision to release him.

The treatment to which Service Ngardjelaï was subjected from the time of his arrest and throughout his detention in Koro Toro prison is absolutely intolerable. This journalist should never have been arrested, and his detention was illegal. Who knows what would have happened if he hadn't met lawyers who knew him? Journalists are subjected to violence and harassment with complete impunity in Chad. We call on the authorities to shed light on Service Ngardjelaï’s arbitrary and abusive detention, the conditions in which he was held and his allegations of torture.

A month and a half after his release, Ngardjelaï still bears the scars of his time in prison. He suffers from intense pain in the spine and has difficulty moving his arms and fingers. His scars are also psychological. Furthermore, he believes that he has been followed and watched since his release, including by people in cars with tinted windows.

Journalism continues to be very dangerous in Chad, which is part of the Sahel, a region in which many areas suffer from the presence of armed groups and a high level of violence. Three journalists have been killed in Chad since 2019, including Narcisse Orédjé, who was fatally shot by individuals in military uniform during the protests of 20 October 2022. His killers have not been arrested. A total of 62 journalists have been arrested in the past ten years and 19 have been physically attacked.

Chad is ranked 109th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2023 World Press Freedom Index.