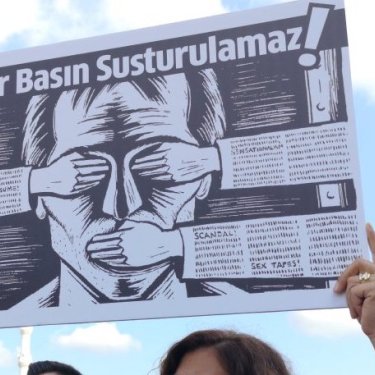

Türkiye’s year-old “disinformation” law has stepped up pressure on journalists

In the following assessment of the way Türkiye’s so-called “disinformation” law has been used since taking effect a year ago, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) concludes that it has proved to be yet another government tool for persecuting journalists, especially investigative reporters and those covering the aftermath of the earthquake in February. This law must be repealed.

In the past year, RSF has registered around 20 examples of the law on disinformation being used as grounds for intimidating journalists, especially investigative reporters, by means of arrests, imprisonment and arbitrary prosecutions.

This law, which took effect on 18 October 2022, introduced a provision into Türkiye’s penal code – article 217 paragraph A/1 29 – that says that “propagation of false or misleading information, contrary to the internal and external security of the country and likely to harm public health, disturb public order, spread fear or panic among the population” is punishable by one to three years in prison.

Then justice minister Bekir Bozdag said the law would only be used in the event of “public order disturbances and attacks on social peace” – concepts that are already interpreted very broadly, or misinterpreted, by the Turkish justice system. But the cases registered by RSF show that it has been used to intimidate local journalists, particularly those covering the February earthquake and elections in May or those doing investigative reporting.

“One year of use has been more than enough to demonstrate that the disinformation law was passed solely in order to further undermine journalistic reporting and investigation. This repressive tool has been used above all against journalists covering the crisis following the February earthquake and the parliamentary and presidential elections held from 14 to 28 May. It has helped to reinforce the climate of intimidation for journalists, who are already subject to many other forms of judicial harassment. Its misuse must stop.”

Erol Onderoglu, RSF’s special Türkiye representative

Those targeted by this law have included Ahmet Kanbal, a reporter with the pro-Kurdish news agency Mezopotamya, who appeared before a criminal court in the southeastern province of Mardin on 18 October. He is being prosecuted for a story with his by-line about “lost ballot box number 1363” – based on statements by observers from various political parties and published on the evening of the 14 May parliamentary elections – and because he only “belatedly” reported that the ballot box had been found. He told RSF that he updated his story that same night with the news of the ballot box’s discovery as soon as he had verified it. He is facing up to three years in prison in this trial, which will resume on 13 December.

Reporter Hasan Sivri is also facing possible imprisonment because on 25 February he posted video footage shot in various regions including Antakya showing the scale of the destruction caused by the 6 February earthquake, while at the same time highlighting a government minister’s threats against his opponents and the fact that there had been no state presence and no rescue services for several days. He is due to appear before a criminal court in Ankara on 12 December.

Journalists Ali and Ibrahim Imat, two brothers who run a local news page on Facebook entitled Mutlu Sehir Osmaniye (Happy City of Osmaniye), were held in Osmaniye prison from 27 February to 30 March for criticising the handling of the aftermath of the earthquake in their province and the failure to take any action for three days, and, in particular, for reporting that “tents sent to the region were uselessly kept in warehouses.” For this, they spent 33 days in a prison in one of the worst-hit regions.

Judicial intimidation

Many journalists are currently the subject of judicial investigations for “disinformation.” They include Mir Ali Koçer, a freelancer, and Zülal Kalkandelen, who reports for the daily Cumhuriyet. Koçer is being investigated for disseminating videos and interviews about quake-hit cities. Kalkandelen is being investigated for writing about the fate of children under state protection who were found in a camp controlled by a religious group.

Some journalists have been acquitted after being brought to trial on a disinformation charge. They include Rusen Takva, an investigative reporter in the eastern Van region, who was acquitted on 6 September. And some journalists, such as BirGün’s Ismail Ari and Medya Koridoru’s Canan Kaya, have seen a court dismiss the case against them.

But, before this happened, they were subjected to months of judicial pressure and attempts to discredit their reporting. This is liable to encourage self-censorship, and therefore constitutes a violation of the freedom of expression that is guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights, as the Council of Europe and Venice Commission pointed out in a joint “urgent opinion” issued on 7 October 2022.