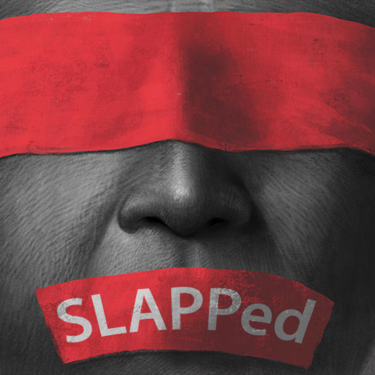

RSF urges EU Member States and European Parliament to agree on effective measures against SLAPPs

As EU negotiations on a directive aimed at combating SLAPPs (gag suits) enter the final stretch, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) calls on the Council of the European Union – representing the governments of EU Member States – to overcome its reluctance and accept the procedural safeguards needed to protect journalists from abusive lawsuits designed to intimidate and silence them.

Almost everywhere in Europe, more and more gag suits are being used to intimidate, scare and silence media and journalists. Media professionals are increasingly exposed to the threat of heavy damages in defamation proceedings. In Greece, several media outlets and journalists investigating government surveillance have been sued by a close adviser to the prime minister, who is seeking damages in the order of 150,000 and 250,000 euros. In 2022, the investment company Eurohold requested 500,000 euros in damages in the defamation suit it brought against the Bulgarian investigative newspaper Bivol.

In response to this problem, the European Commission adopted a recommendation for Member States in April 2022, but they have been dragging their feet. A European directive on SLAPPs (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) is intended to reinforce this initiative.

The Council and the European Parliament must agree on the directive’s final wording in the concluding phase of negotiations due to begin tomorrow (12 July). Today, MEPs approved a protective version of the directive by a very large majority (498 for, 33 against and 105 abstentions). But the Council has already watered down the European Commission’s proposed version to the point that the directive would be an empty shell providing journalists with no protection against gag suits. Key provisions have been deleted.

“If Member States do not backtrack, this directive will be a complete waste of time. Reinstating the key provisions that were removed is essential in order to prevent continued misuse of the courts to silence journalists.”

The Council has reduced the directive’s scope enormously by limiting it to cross-border cases, in other words, to cases where the two parties concerned are domiciled in different Member States, which is not the case in the vast majority of SLAPPs.

The EU lacks the authority to legislate on strictly national matters but the Commission has introduced the notion of “cross-border implications,” which has been accepted by the European Parliament but not by the Council. It would mean that a SLAPP with implications in more than one country – such as one involving money laundering or cross-border pollution – would fall within the directive’s scope.

Parliament has even expanded the applicability of “cross-border implications,” saying it should take effect as soon as the subject of a lawsuit is “accessible via electronic means.” It is essential that Member States should accept this notion of cross-border implications, or else the directive’s procedural safeguards will apply to few concrete cases.

Civil actions brought in the context of criminal proceedings have also been excluded by the Council from the directive’s scope, further reducing its potential applicability.

The mechanism under which a baseless gag suit could be quickly dismissed has been weakened by a restrictive definition, and the ability to appeal against a refusal to dismiss proceedings quickly has been removed. This mechanism is the key procedural safeguard that would prevent those who bring SLAPPs from prolonging their lawsuits for years, thereby leaving a financial and psychological threat hanging over the journalists and media targeted.

The Council has also removed a provision under which a journalist or a media would be able to seek full compensation for the material and psychological damage they suffer as a result of a baseless gag suit – a provision that would serve as a major deterrent to those considering bringing such lawsuits.

Finally, the deadline for incorporating the directive into the national law of the Member States has been extended to three years, as against the usual two years – an unwelcome extension at a time when the number of SLAPPs against journalists is on the rise.