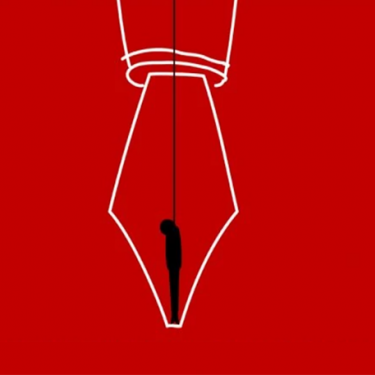

Journalists face archaic sanction of capital punishment in some parts of the world

Four Yemeni journalists and an Iranian editor are under sentence death and await execution. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) condemns the use of the death penalty, an antiquated form of punishment, to threaten journalists in some parts of the world.

The Yemeni journalists Abdul Khaleq Amran, Akram Al-Walidi, Hareth Humaid and Tawfiq Al-Mansouri were found guilty of espionage by a Houthi court in Sanaa and received the maximum sentence in April this year. The Iranian government critic Rouhollah Zam, who ran AmadNews, a website and a channel on the messaging platform Telegram, learned of his sentence in Tehran for “corruption on earth” just one week ago.

“It is difficult to imagine that, in 2020, journalists are still being sentenced to this most archaic and barbaric of penalties,” said RSF Secretary-General Christophe Deloire. “Every year the worldwide abolition of the death penalty moves a little closer and threats to execute journalists because of their work should be consigned to history instead of being news. Governments that favour abolition should join forces to finally make redundant an outdated penalty that is the worst possible obstacle to freedom of the press.”

This latest conviction brings the number of journalists currently on death row to nine. The previous case was in September 2017, when the South Korean journalists Son Hyo-rim and Yang Ji-ho, as well as the publishers of their newspaper Kim Jae-ho and Pang Sang-hun, were condemned to death in absentia “with no right of appeal” for publishing a positive review of a book about North Korea’s growing market economy.

It is unlikely that these sentences will be carried out, although in Iran, among the countries with the highest number of executions, the death penalty is a sword of Damocles hanging over journalists. In the past 20 years at least 20 journalists, bloggers and citizen-journalists have been sentenced to death.

Iran’s Islamic penal code, based on the Sharia, provides for capital punishment for a variety of offences. Soheil Arabi, recipient of the 2017 RSF Press Freedom Prize in the citizen journalism category, was sentenced to death in 2014 for “insulting the Prophet of Islam, the Shiite Holy Imams and the Koran”. Adnan Hassanpour, who worked for the Iranian Kurdish-language weekly Asou, was sentenced to death in 2007 for spying.

2000, Hassan Youssefi Echkevari, an Islamic cleric and journalist who worked for the monthly magazine Iran-e-Farda, was tried and sentenced to death for being a "mohareb", “one who fights God”. He was accused of subversive activities against national security, defaming the authorities and attacking the prestige of the clergy.

All these sentences were commuted in the end to long prison terms, sometimes life, but Iran still holds the dubious record for the number of journalists officially executed in the past 50 years. In the aftermath of the Islamic revolution in 1979, at least 20 journalists close to the shah’s regime, such as Ali Asgar Amirani , Simon Farzami and Nasrollah Arman, and others associated with left-wing circles including Said Soltanpour and Rahman Hatefi-Monfared were executed by firing squad.

Iran’s neighbour Iraq is the most recent country to have carried out the death penalty on a journalist. In March 1990, the British journalist Farzad Bazoft was executed on charges of spying for British and Israeli intelligence.

Since then, press freedom and human rights organizations have campaigned on many occasions on behalf of numerous journalists and bloggers to prevent the worst. In Mauritania, the blogger Mohamed Cheikh Ould Mohamed Mkhaiti was sentenced to death in 2014 for apostasy. The sentence was confirmed on appeal in 2016 only to be commuted to two years’ imprisonment in 2017.

In Myanmar, the sports journalist Zaw Thet Htwe was sentenced to death in 2004 for sending information to the International Labour Organisation. His sentence was later commuted to three years’ imprisonment by the Supreme Court on appeal.

Major campaigns in favour of a number of symbolic cases, such as that of the photographer Shawkan in Egypt and the Radio France Internationale correspondent Ahmed Abba in Cameroon’s Far North region, may have helped to pre-empt the judges’ inclination towards the death penalty in these countries.

In both cases, as well as those of the journalists Ali Al-Omari in Saudi Arabia and Ali Mohaqiq Nasab in Afghanistan, prosecutors requested the death penalty for blasphemy and terrorism-related offences. Their final sentences, however, did not follow these deadly requests.

In China, which is one of 54 countries that still have the death penalty and holds the record for the largest number of executions, the last journalist executed surprisingly was the Associated Press correspondent Yin-Chih Jao in 1951. However, long prison terms and life sentences imposed on journalists, often in appalling conditions and accompanied by ill-treatment, amount to death sentences in reality. In 2017, the Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo and the blogger Yang Tongyan died as a result of lack of medical care in prison.

In Latin America, where most countries have abolished or partially abolished the death penalty over recent decades, no journalists have been sentenced to death for 50 years. However, the direct or indirect participation of governments in extra-judicial executions of journalists by hitmen, mercenaries or crime gangs is a recurring fact in several countries in the region, including Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Brazil and Colombia.

Journalists have also been executed by non-state groups. The barbaric decapitations of the American journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff by the Islamic State group in August 2014 in retaliation for US intervention in Iraq and Syria are seared in people’s memories.

In Afghanistan, a dozen local journalists and media workers have been executed by the Taliban since 2001. Among them was the BBC correspondent Abdul Samad Rohani, shot dead in 2008. The journalist Ajmal Naqshbandi and Sayed Agha, who worked as interpreter and driver respectively for Daniele Mastrogiacomo, a journalist with the Italian newspaper La Repubblica both had their throats cut.

- Africa

- Mauritania

- Cameroon

- Americas

- Mexico

- Colombia

- Chile

- United States

- Argentina

- Middle East - North Africa

- Egypt

- Iran

- Asia - Pacific

- North Korea

- South Korea

- China

- Afghanistan

- Technological censorship and surveillance

- Disinformation and propaganda

- Violence against journalists

- Legal framework and justice system

- News

- Attacks

- Organised crime

- Internet