New communication code puts Gabon’s media in straitjacket

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) is very concerned about Gabon’s controversial new “communication code,” which exposes the country’s media to pressure without giving journalists the legal guarantees they need to practice their profession freely.

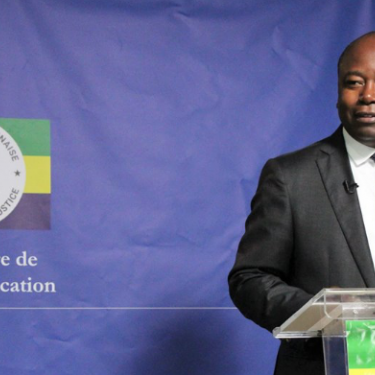

Communication minister and government spokesman Alain-Claude Bilie Bi Nzé announced last week that the new law, which he said would enable journalists to work with more freedom and responsibility, will take effect on 2 January, although it has already technically been in force since its promulagation by decree during a parliamentary recess last August.

The announcement came a month after a spectacular police raid on the Echos du Nord opposition newspaper on 3 November over a controversial report about Gabonese intelligence chief Célestin Embinga, who has since been fired. The newspaper’s editor said she was tortured during interrogation to make her reveal her sources.

It is hard not to see the announcement as a message to journalists who are openly critical of the government, especially those who live abroad to avoid persecution like Echos du Nord publisher Désiré Ename. Article 16 of the new code specifically prohibits anyone residing outside Gabon from running a Gabonese publication or producing news for publication in Gabon.

However, article 16 is far from being the new code’s only shortcoming.

A code with many flaws

“Gabon’s communication code restricts the freedoms of media and journalists without providing a clear legal framework that protects the media profession,” said Cléa Kahn-Sriber, the head of RSF’s Africa desk. “The vague wording, the imprecise definitions of offences and the constraints imposed on the media just reinforce the threat to free speech and encourage self-censorship.

“We provided the Gabonese government with a series of recommendations on a first draft of the communication code, with the aim of improving respect for national and international norms. Unfortunately they have not been taken into account in the final version.

“We acknowledge that there has been some progress, such as article 15 banning members of the government and public sector from owning media outlets, and the decriminalization of media offences. But the code contains many obstacles to freedom of information. We therefore urge the government to amend this law so that it really protects the rights and duties of Gabon’s journalists and citizens.”

A code that covers too broad an area

The new code concerns not only the media but also all other forms of broadcast, print, digital and cinematographical production, while article 3 requires them to “contribute to the projection of the country’s image and national cohesion.”

The code is often imprecise in its wording and often uses vague concepts. Article 11, for example, says censorship is “forbidden except in cases envisaged by the law” but no law is ever cited. Article 181 says “abuses of freedom of expression” are penalized but they are not defined. Attacking “national unity” is banned in article 95, and journalists and publishers are required to “promote” national unity, but it is also left undefined.

It is impossible to know the penalties to which media and journalists are exposed for specific offences. Articles 192, 194 and 195 list fines ranging from 500,000 francs (750 euros) to 10 million francs (15,000 euros) for each “offence as regards (...) the creation of a communications company (...) committed with regard to communication (...) or with regard to publishing, posting or printing.”

But the “specific acts constituting the penalized offences (...) and the penalties” themselves are left to the government to decide. Article 199 says they will be determined “by cabinet decree.”

Nitpicking

This legal uncertainty is compounded by the code’s attempts to increase controls over journalists and define how they should work.

Journalists are no longer allowed to use a pseudonym to maintain anonymity as they will have to officially register their pseudonym.

Article 87 requires journalists to “safeguard public order and promote national unity,” thereby limiting their freedom to criticize and their duty to play a watchdog role. This is compounded by a restriction on access to the journalistic profession. The code requires journalists to have a qualification “approved by the state” (without providing further detail) or to have worked for five years in a media outlet “recognized by the state” (again without further detail).

The articles about digital media use equally vague terms that inflict legal uncertainty on bloggers, citizen journalists and all others who post content online.

Subjugated media

Article 75 places privately-owned media outlets “under the control of the minister responsible for communication” although they are already subject to private enterprise law. The nature of this control – administrative, legal, financial or editorial – is not specified.

The burden of self-censorship is distributed equally between journalists, disseminators and printers, inasmuch as article 180 says they are all “jointly responsible” for media offences. Will printers take the risk of printing a newspaper critical of government policy if they could be convicted of violating the communication code?

Gabon is ranked 100th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2016 World Press Freedom Index, five places lower than in 2015.