Death of the daily press briefing: How the White House is closing the door on the American people

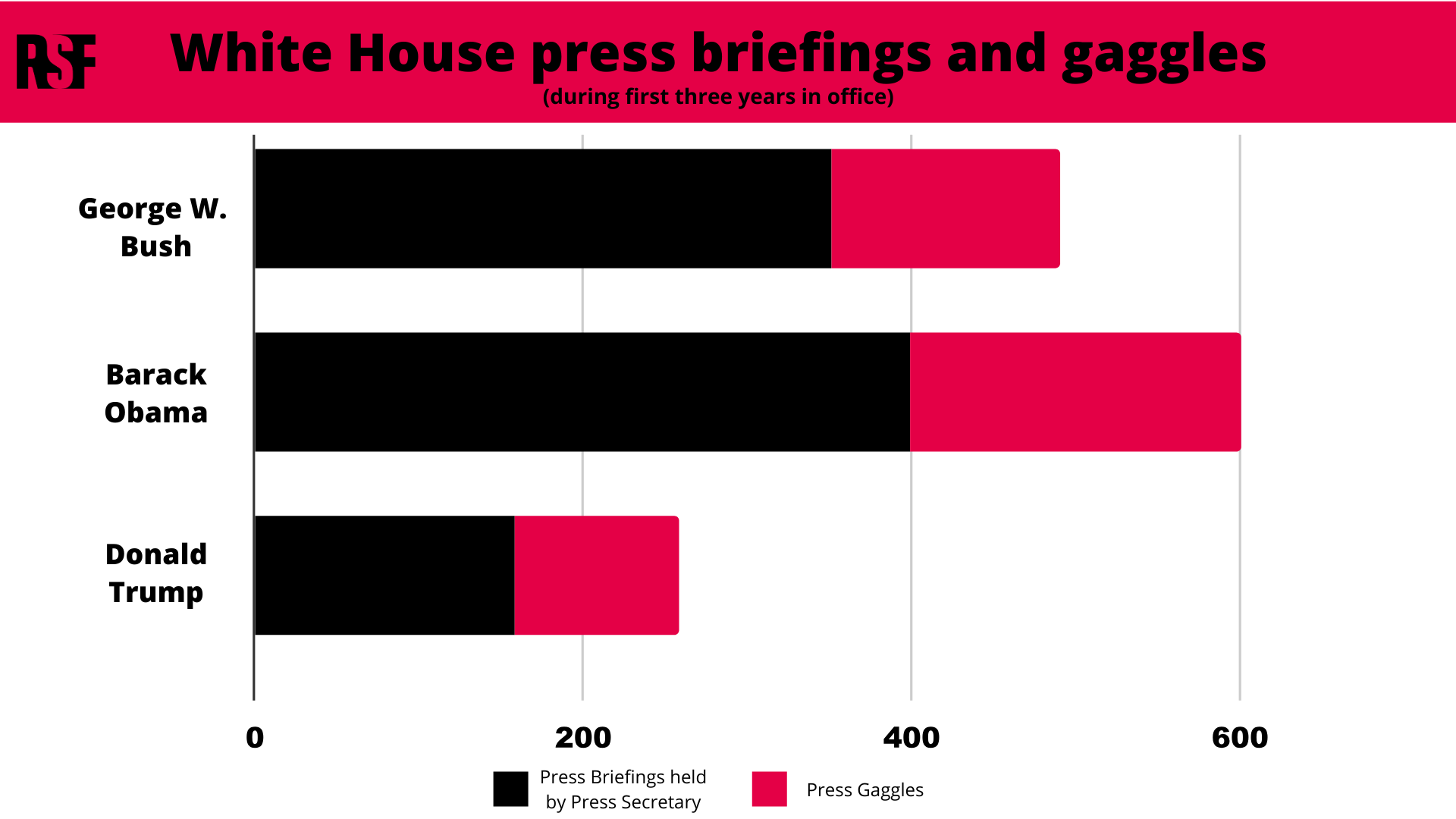

One year since the last official White House press briefing, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) published on March 11 an analysis of the Trump administration’s attempts to strategically restrict press access to the White House. Prior to ending the daily televised press briefing altogether, President Trump held less than half as many as the previous two administrations during their first three years in office.

March 11 marks an entire year since the Trump administration has held a televised White House press briefing led by a press secretary, signaling a drastic break from long-standing White House tradition with the Washington-based press corps. President Trump has held less than half as many of these traditional press briefings—the daily, televised briefings held by a press secretary—during his tenure as the two presidential administrations prior. Even before this administration ended the traditional press briefings altogether, the frequency of the White House briefing—an institution built over a century—was in steady decline under President Trump. Starting in 2017, the Trump White House increasingly replaced the traditional press briefings with other formats of press engagement, including “chopper talks” as the president walks between Marine One or Air Force One and the White House, briefings led by an administration official, and off-camera press gaggles, which are less formal opportunities for a press secretary or administration official to brief reporters. All have been used by the Trump administration in an attempt to control the political narrative and evade accountability.

“On the one-year anniversary of the last official, televised White House press briefing, RSF is calling on the Trump administration and all future presidential administrations to re-establish this long-standing American democratic tradition,” said Dokhi Fassihian, Executive Director of RSF USA. “President Trump’s use of ‘chopper talks’ and other press formats create the illusion of transparency, but this is smoke and mirrors. The reality is that a once-guaranteed, direct line of sight into the government has been extinguished.”

A steady decline under Trump

Before holding the last press briefing with a press secretary on March 11, 2019, the number of Trump administration press briefings was already in steady decline. The Trump White House had a total of 158 press briefings during which a press secretary took questions in President Trump’s first three years in office, compared to 399 under Barack Obama and 351 under George W. Bush during their first three years. Trump administration press briefings held by a press secretary shrank from 93 in 2017, to 63 in 2018 and only two in 2019. Martha Kumar, director of the White House Transition Project and a scholar on the US presidency, explained the implications of this chilling trend to RSF. “A briefing fills a very important role because it holds an administration to account to explain what they did and why they did it,” Kumar said. “It informs the public so it's not just that reporters lose when there is no briefing but the public loses. We know what's on the president’s mind, but you need to know what's going on in an administration.”

While correspondents generally have extensive source networks and avenues into the White House, the press briefing is an opportunity for the press secretary or other administration official to address the press corps and take questions from reporters, generally on-camera and in the James S. Brady Press Briefing Room. The once-guaranteed, traditional televised press briefing led by a press secretary gave reporters daily access to a spokesperson for the president who could answer questions on the full spectrum of issues, representing a level of transparency and accountability that reporters and the American public had come to expect. These briefings ensured accountability, because as Richard Wolffe, a White House correspondent for MSNBC under President George W. Bush and author of several books about Barack Obama, told RSF, “Video is harder to dispute than an audio recording.” Its importance was undeniable, especially in an administration that coined the term “alternative facts” and regularly accuses major media outlets of being “fake news.”

The Trump White House increasingly chose, however, to replace traditional press briefings for formats like “chopper talks” that enable the administration to better control its political narrative and evade accountability. “Chopper talks,” when President Trump answers questions in front of Air Force One or Marine One on the White House Lawn as the motor or helicopter’s blades are whirring, happen at the president’s will and rarely last more than a few minutes. Presidential press conferences similarly give the president publicity and an opportunity to give remarks while allowing journalists opportunities to ask questions, albeit in a more controlled setting. The press gaggle, an off-camera, on-the-record opportunity for the press secretary, an administration official or the president to field reporters’ questions, has historically been a supplement to the daily televised briefings, not a replacement.

The murder of Washington Post contributor Jamal Khashoggi, the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh and US midterm elections all took place without a traditional press briefing at the end of 2018. This increasingly frequent absence of a press secretary at the briefing room podium drew the ire of reporters and media analysts, who began keeping regular counts of the days since the last White House press briefing. There were only two televised briefings with a press secretary in all of 2019, and Stephanie Grisham, who started her tenure as press secretary in July, has not held a single televised briefing.

History of the briefing

White House officials have routinely briefed the press since at least the 19th century, with the earliest records of such briefings dating back to Grover Cleveland’s administration. It began in 1896 when William Price, a reporter for the Washington Evening Star, positioned himself outside the White House trying to pick up stories and interviewing guests on the grounds. The tactic became popular among Washington-based reporters and eventually evolved into the first iteration of the White House press corps. Finally, under the Theodore Roosevelt administration, the press corps was granted a permanent space in the West Wing to conduct their business.

Woodrow Wilson, though known for his aversion to the press under certain circumstances, was the president who established the regular press secretary-led briefings. Though he stopped holding press conferences altogether after the United States entered into World War I, it was during this time that his personal secretary, Joseph Tumulty, began to hold daily press briefings and formalized the White House press briefing that Americans know today.

The first official press secretary designated to speak on the president’s behalf was George Akerson, who took office in 1929 during the presidency of Warren Harding. This, along with the founding of the White House Correspondents Association in 1914, solidified the press briefing as an institution. There have been 32 press secretaries since 1929, and each has had their own unique relationship with the press corps.

In 1995 President Bill Clinton’s Press Secretary Mike McCurray began televising the daily press briefing. The Obama, Bush Jr. and Clinton administrations shared a common foundational relationship with the press, holding daily televised briefings, as well as regular morning on-the-record press “gaggles,” which were less formal, off-camera briefings. “There was a very well-established rhythm,” said Wolffe. While the Trump White House had a similar routine, there was less consistency from the start.

Controlling the narrative

Though the press secretary has traditionally been entrusted by presidents to speak on their behalf, this has not been to the advantage of a president who often lacks a clear or consistent message and contradicts his press secretaries or other administration officials. In President Trump’s White House, control is key. Kumar described this president as the “lead communicator” for the White House, noting his use of social media as his primary mode of communicating directly with the American public.

President Trump’s use of Twitter to make major policy announcements or attack his political opponents is the starkest example of the way he has usurped the White House’s messaging. He often takes advantage of opportunities to speak to the press, such as presidential press conferences and on-the-record meetings in the Oval Office, to ensure he is his administration’s main spokesperson. For example, by the time the president was impeached on December 18, 2019, there hadn’t been an on-camera briefing with a press secretary in more than nine months, but President Trump took questions for about 20 minutes in the Oval Office the following day, calling his impeachment a “hoax” and a “phony deal.”

The growing decline of White House press briefings that began in mid-2018 was coupled with a simultaneous rise in President Trump’s “chopper talks,” which has become another favorite mode of direct communication for the president. Unlike previous administrations, the Trump White House archives the transcripts of the president’s on-the-go conversations with the press corps alongside those for press conferences, briefings and gaggles, giving the impression that these are actual press events. However, “chopper talks” should not be considered legitimate replacements for traditional access. The talks take place as the president is leaving or returning to the White House, a time and space-limiting context that gives him the ability to reject questions at his own whim.

Evading accountability

Even before it ended the traditional press briefings altogether, the Trump administration had already started replacing them with press gaggles and briefings led by other administration officials in an effort to control the day’s story. When leaked memos written by former FBI Director James Comey were published by the Associated Press on May 17, 2017, the White House did not hold an on-camera briefing with then-Press Secretary Sean Spicer, opting for a press gaggle with him instead. While gaggles are valuable opportunities for reporters to ask questions, they lack the level of transparency that on-camera press briefings afford. The gaggle is off-camera, prohibits video and audio, and is occasionally held on-background, meaning the administration officials fielding questions are not identified. The memos presented the strongest evidence to date that the president had tried to influence the Justice Department investigation into links between his associates and Russia. It is thus unsurprising that the White House would opt out of a press secretary-led on-camera briefing—not having another until June 2.

Twenty-three percent of President Trump’s press briefings have been held by someone other than his press secretary, compared to 14 percent under Obama and 4 percent under Bush. Today, these are the only briefings the White House holds, and they are not guaranteed every day. This has eliminated the White House press corps’ daily opportunity to engage with the press secretary, whose sole responsibility was to speak to reporters on the full range of domestic and foreign issues on the president’s behalf. However, briefings held by administration officials limit the types of questions reporters can reasonably ask, narrowing the scope of the briefing to the advantage of the White House during a difficult news week. A day after Hurricane Maria touched down in Puerto Rico in 2017 and devastated the US territory, the White House held unrelated two briefings, one with the treasury secretary and one with the US ambassador to the United Nations, during which the hurricane was not discussed. Stewart Powell, former president of the White House Correspondents Association between 1998-1999, told RSF that this is strategic. “[Administration officials] want to change the subject. They want that to be the story of the day.”

In addition to replacing the traditional press briefing, the president has used more explicit tactics to influence press coverage. The Trump administration has retaliated against specific news outlets and journalists for their critical coverage barring them from the White House on multiple occasions. In February 2017, only one month after his inauguration, President Trump blocked news organizations like the New York Times and CNN from an informal briefing. The following year, in November 2018, the White House temporarily and arbitrarily revoked CNN correspondent Jim Acosta’s press pass and revoked Playboy correspondent Brian Karem’s credentials in August 2019. Referring to the revocation of his press pass, Karem told RSF, “It should be a warning to others that this president does not want people covering him that don’t compliment him.”

Conclusion

In his time in office, President Trump has strategically restricted press access to the White House by ending the long-standing tradition of a daily televised press briefing led by a designated press secretary. This critical institution has been replaced by other forms of press engagement that give the illusion of access and transparency, but rather limit the time and scope for journalists to ask questions of the administration. In particular, the president’s use of “chopper talks” and other self-styled on-camera events suggest a president who is available to journalists even when on the move, but these engagements are short and performative, rather than substantive. Similarly, press briefings held by administration officials give the impression of a White House committed to openly communicating with the press while in fact limiting the scope of the issues officials can address and questions reporters can have answered.

The US ranks 48th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2019 World Press Freedom Index.