Call for independent probe into tribal reporter’s murder in Jharkhand

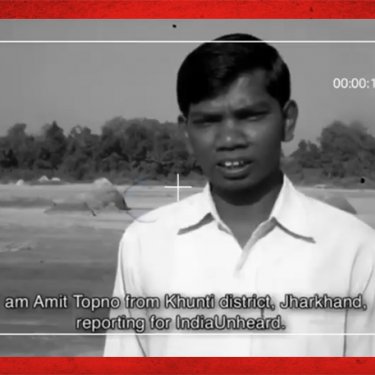

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) calls on the Indian authorities to set up an independent enquiry into the murder of Amit Topno, a tribal community reporter in the eastern state Jharkhand, because the local police investigation has stalled. Topno’s body was found at the side of a road in Ranchi, the state’s capital, exactly one month ago today.

A member of India’s Adivasi (indigenous peoples), Amit Topno was from Khunti, a district 40 km south of Ranchi, where he covered his Adivasi community’s resistance against abuses and exploitation by the local authorities and businessmen.

When his body was found in the Ranchi neighbourhood of Doranda on 9 December, it bore two bullet wounds, one in the head and one in a shoulder, but no signs of a prior struggle, not even a scratch, and Topno’s money was even found on the body.

A Doranda police station representative said at the time it looked like a “premeditated murder.” When contacted a month later by RSF, the Ranchi police superintendent had nothing to add. “We don’t have any leads on the case,” he said. “His phone, his car and his ID are still missing.”

“Either the police are not competent enough or they don’t want to say,” said Deepak Bara, the coordinator of the Video Volunteers participative website in Jharkhand, with which Topno had collaborated for a long time, as well as being the Khunti correspondent for NewsCode and OK Times.

“He didn’t report any threat to us,” Video Volunteers founder Jessica Mayberry told RSF. “His reports were often on controversial topics, with apparently lots of visibility in the Hindi media.” Topno was a feisty reporter who was always ready to denounce abuses affecting his community, including illegal mining, trafficking in human beings, alcohol smuggling and ethnic discrimination.

“Amit Topno’s reporting clearly annoyed certain people and, in the absence of any other motive, it is time that investigators focused on the hypothesis that his murder was linked to his work as a journalist,” said Daniel Bastard, the head of RSF’s Asia-Pacific desk.

“In view of the lack of action by the local police, we call on the Indian authorities to immediately appoint a special team to carry out an independent investigation and identify those responsible for this despicable crime as soon as possible.”

Sensitive subjects

The sensitive stories covered by Topno included the growing conflicts with the local authorities resulting from emancipation movements within the Adivasi minority and their attempts to assert their special rights under their “Scheduled Tribes” status, which is supposed to help them combat discrimination.

In recent months, he had been covering the “Pathalgadi” movement, in which Adivasi have been erecting large stone slabs at the entrance to their villages inscribed with the articles of the Indian constitution that accord special privileges to the “Scheduled Tribes.” These articles are routinely violated and, in Topno’s district, Khunti, the violations increased after gold was discovered there, fuelling local authority interest, Bara told RSF.

Dangerous truth?

Topno and Bara had covered an alleged gang-rape in Khunti in June 2018, for which the police immediately arrested several Pathalgadi movement leaders although there was no evidence against them.

“The police told the victims not to talk to NGOs and journalists,” Bara said. “Amit thought this gang-rape incident was a conspiracy by the local government to crackdown on the Pathalgadi movement.” Did Topno get too close to a dangerous truth? Only a fully independent investigation could resolve the suspicions surrounding this case.

Just six weeks before Topno’s murder, Chandan Tiwari, a journalist based in Chatra, a district in the north of Jharkhand state, was beaten to death after covering a local case of corruption.

RSF issued an “incident report” in July about the threats to India’s position in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index, in which it is currently ranked 138th out of 180 countries.