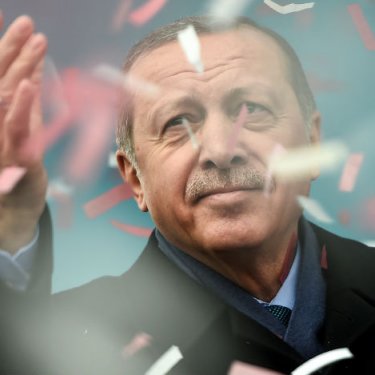

With no media pluralism, referendum road clear for Erdoğan

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) questions the validity of next Sunday’s referendum in Turkey on changes to its constitution because of the massive curbs on freedom of information. The outcome will be crucial for the country’s future but the government’s tight grip on the media has deprived the public of a proper debate.

Human rights groups are alarmed by the proposed constitutional amendments because they increase the president’s powers and eliminate essential checks and balances. The Council of Europe has described the changes as a “dangerous step backwards” towards a “one-person regime.”

But the public debate has been completely inadequate because the referendum campaign has coincided with an unprecedented crackdown on Turkey’s independent media outlets.

“The drastic curtailment of media pluralism and the still-growing pressure on critical journalists have reduced the space for democratic debate considerably,” said Johann Bihr, the head of RSF’s Eastern Europe and Central Asia desk.

“How can Turks make an informed choice without being able to access complete media coverage and a wide range of opinion? Democracy requires media freedom. It must be restored at once.”

Without pluralism, a one-sided campaign

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) has been observing the campaign since the start of March and issued an interim report last weekend. Shortly before its release, Michael Georg Link, the head of the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, told Deutsche Welle that the campaign was being “handled one-sidedly” in the Turkish media.

The state of emergency declared after last July’s abortive coup attempt has eliminated almost all pluralism in Turkey. More than 150 media outlets have been closed by force for allegedly collaborating with “terrorist” organizations.

Some, such as Zaman, Bugün, Millet and Taraf, were alleged to have collaborated with the movement led by the US-based cleric Fethullah Gülen, which is accused of being behind the coup attempt. Others, such as İMC TV and Hayatın Sesi TV, were alleged to have collaborated with the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

As a result, entire swathes of the media landscape have been liquidated at the stroke of a pen, depriving many segments of the population of the diversified sources of news and information they had come to rely on.

These devastating blows capped an offensive that began a decade ago in which leading media outlets were either taken over by the state or were bought up by pro-government investors. In the process, political meddling, self-censorship and dismissals of critical journalists have all become routine.

According to the Media Ownership Monitor project carried out by RSF and the Bianet news website, seven of the ten owners of the most viewed national TV channels have direct ties to President Erdoğan and his government.

Balance abolished by decree

In a decree that took effect on 10 February, the government abolished article 149-A of Law No. 298, under which the broadcast media were required to provide all sides with equal airtime during an election campaign.

By scrapping this legal (and ethical) obligation, under which violations were punishable by a fine or suspension, the authorities have lifted the last safeguard preventing the pro-government media from campaigning openly for a “yes” vote in the referendum. The Electoral High Council helpfully waived the constitutionally required one-year delay before any amendment to electoral law can take effect.

State media campaign for “yes”

The privately-owned media are not the only ones campaigning for a “yes” vote. On 27 March, a member of the HDP, a left-wing, pro-Kurdish party, filed a complaint with the High Council for Broadcasting (RTÜK) about public TV channel TRT Haber’s biased coverage.

The HDP complaint said that, from 1 to 22 March, TRT Haber dedicated 1,390 minutes to President Erdoğan and 2,723 minutes to the ruling AKP party, as against 216 minutes to the main opposition party, the CHP, and 48 minutes to the nationalist MHP party. TRT Haber simply ignored the HDP during this period.

CHP parliamentarians have announced that they have also filed a complaint against TRT Haber. The party’s leader, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, was invited to speak on the air on 7 April but had to wait for half an hour until live coverage of an unexpected statement by President Erdoğan had finished.

“We had to go through [Deputy Prime Minister] Numan Kurtulmuş in order to take part in this broadcast,” he said. “TRT must demonstrate impartiality... This is unacceptable. The taxes I pay contribute to this TV channel’s budget.”

“No” voters intimidated, demonized

Incidents throughout the campaign have created a climate of intimidation for supporters of a “No” vote. Groups of pro-AKP activists have attacked their stands and meetings. They have been denied the use of conference rooms. They have been subjected to police raids. And journalists and media outlets that support a “No” have not been exempted.

In mid-February, the newspaper Hürriyet refused to print an interview with Nobel literature laureate Orhan Pamuk, in which the writer said he would vote against the constitutional amendments.

That was just a few days after the Doğan media group, Hürriyet’s owner, fired İrfan Değirmenci, a leading presenter on Kanal D TV, because he had explained on Twitter why he planned to vote “No.” Doğan said Değirmenci violated the principle of impartiality because he was a presenter, not a commentator.

Yusuf Halaçoğlu, a former parliamentary representative who was expelled from the MHP party for criticizing its official line of support for a “Yes” vote, was barred from a HaberTürk TV programme in early March although his participation had originally been planned.

The pro-government media do not hesitate to demonize “No” supporters. Media outlets such Takvim, Akşam, Güneş, Sabah, Yeni Akıt and Yeni Şafak lavish coverage on the government’s virulent attacks on the opposition.

They take their line from Erdoğan, who portrays the proposed constitutional amendments as “a response and a solution” to the July 2016 coup attempt. On 11 February he said: “Those who say ‘no’ to the referendum will, in one way or another, be positioning themselves alongside the 15 July [coup supporters]. Let that be clear.”

Using the government’s derogatory acronym “FETÖ” to refer to the Gülen movement, Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım went even further on 5 February, saying: “FETÖ and the PKK say no. That’s why we say yes. The people will respond via the polls to those who say yes to separatism.”

The demonization of “No” supporters is sometime literal. A professor of religion, Vehbi Güler, said on the pro-government channel TV24in early February: “Satan in his revolt against God also said No!”

Turkey is ranked 151st out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2016 World Press Freedom Index. Although the situation of the media is now critical, it was already disturbing before the July 2016 coup attempt and the ensuing state of emergency declared in its wake.