Egyptian websites try to resist blocking

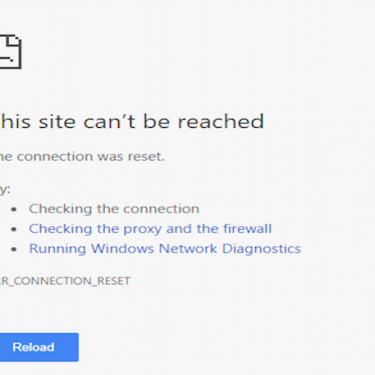

Egypt’s independent online media are trying to resist and circumvent an unprecedented wave of website blocking and censorship by the Egyptian government that Reporters Without Borders (RSF) regards as a grave violation of free speech and the freedom to inform.

“Egypt is currently in a digital black hole,” said Lina Attalah, the founder of Mada Masr, an influential Egyptian online newspaper publishing in English and Arabic that was one of the first news sites to be blocked by the government.

The offensive against the Egyptian Internet began with the blocking of about 60 sites on 24 May and has been growing ever since. According to the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE), 123 sites are currently censored. Never have so many sites been blocked at the same time, except when the government disconnected the Internet altogether during the 2011 uprising.

“This act of censorship on a scale without precedent in Egypt is depriving the public of news and information that is independent and free of government control,” said Alexandra El Khazen, the head of RSF’s Middle East desk.

“The blocking of news websites is continuing the draconian policies of a regime that has turned Egypt into one of the world’s biggest prisons for journalists. We call on the authorities to clearly and officially state the reasons for all this blocking and to quickly end what appears to be purely political censorship.”

More than half of the 118 currently-blocked websites are news sites. Most are regarded as the media outlets or platforms of the military regime’s bugbears such as Qatar and Islamists. But some are just Arabic or English-language media whose independence irritates the regime.

They include political party websites and the sites of the Tor Project and VPN providers whose software enables users to bypass blocking by masking their IP address and appearing not to be in Egypt.

“The blocking is so extensive that it reaches all websites publishing content not subject to prior filtering by the Egyptian authorities,” Lina Attalah said. “Even the petitions site Avaaz has been blocked.”

Ways to bypass blocking

Censored online media are trying to keep their content available to Egyptian readers via the VPNs that are still accessible. But these censorship circumvention methods are not yet widely used in Egypt so their impact is limited.

Al Bedaiah, an online Arabic-language newspaper that specializes in covering social conflicts and political prisoners, has seen a drastic fall in its readership now that it is only accessible to those using VPNs.

“Before we had an average of 1,000 unique visitors at any one time but now there are fewer than 20,” Al Bedaiah editor Khaled el Balshy said. “We are producing fewer articles than before. It’s depressing for me and my colleagues but we continue to work with determination despite the blocking.” He said he has considered creating a new site but thinks it will also be blocked.

To keep their articles accessible to readers, some media such as Mada Masr post them on related websites such as the French site Orient XXI or on Facebook, which is very popular in Egypt.

“Since the blocking, we have seen a big increase in the number of our Facebook followers,” Attalah said. “But we have no illusions. We know that we are not disseminating as much content as before.”

Facebook is an ingenious if rather impractical solution but how much longer will it work? Last spring, the Egyptian parliament drafted a bill that would make access to social networks such as Facebook and Twitter conditional on being registered with the authorities.

Article 19 of a proposed electronic crime law provides for blocking any website that is deemed to threaten national security interests, a phrase that is already widely used in political trials. The parliament has been debating the bill for some time but has not yet passed it.

Illegal blocking?

For the time being, there is neither any specific legislation nor has there been any official statement from the authorities about the blocking, aside from the publication of a “report” on 25 May that refers to authorization to block certain sites for a series of reasons linked to the need to combat terrorism.

As a result, and for want of a negotiation window with the security services, some websites have initiated legal actions against what they hold to be an arbitrary and illegal measure.

“We would like to know what the grounds are for a decision of this kind,” said Attalah, whose website, Mada Masr, is among those that have filed a complaint with the attorney-general and have requested an explanation from the administrative court. The free speech group AFTE also filed a complaint on 18 June.

Unless their website gets unblocked soon by a judiciary measure, Masr al Arabiya, an independent Egyptian news website, knows it is on the verge of closing. Some of their readers may use VPNs, but this is far from enough. Adel Sabry, the editor in chief, is extremely concerned : he said the security services have been pressuring not only its advertisers but also the politicians and soccer players it interviews, depriving the website of its revenues and content in one go. Sabry has had to lay off nearly half of his 64 journalists and says he will have to shut the website down.

The blocking has come at a time of domestic political tension fuelled by next year’s presidential election, an economic crisis, the political crackdown, continuing terrorist attacks and recent nationalistic unrest among sectors of society whose support for the regime has been undermined by its decision to cede two small Red Sea islands, Tiran and Sanafir, to Saudi Arabia.