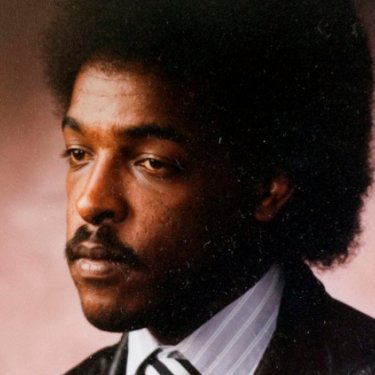

Dawit Isaak: RSF deplores final refusal by Swedish prosecutor to investigate journalist’s 20-year detention in Eritrea

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) is considering its options after a definitive refusal by the Swedish prosecutor’s office to open an investigation into crimes against humanity in the case of Dawit Isaak, a journalist with Swedish and Eritrean dual nationality who has been held incommunicado and without trial for 20 years in Eritrea.

In a decision issued on 29 November, Stockholm’s deputy prosecutor-general again recognized that “there are reasons to suspect that crimes against humanity in the form of enforced disappearances have been committed against Dawit Isaak.” But, arguing that it would be impossible to investigate these suspected crimes, she definitively confirmed the refusal by the Swedish prosecutor’s office to open an investigation in response to the complaint filed by RSF in October 2020.

In her decision, the deputy prosecutor-general describes at length the difficulties that prevent an investigation from being opened. In particular, she insists that Eritrea is unlikely to cooperate and asserts that the suspects would not come to Sweden of their own accord.

RSF regards these arguments as surprising and contradictory. One of the suspects targeted by the complaint, Eritrean foreign minister Osman Saleh, visited Stockholm in October, and another suspect, presidential adviser Yemane Gebreab, recently visited several European countries, where he could have been arrested under a European warrant if Sweden had decided to issue one.

Furthermore, the Swedish prosecutor’s office has already opened investigations into cases in other countries where there was hardly any more probability of cooperation by the authorities in those countries, and it did so even though the victims were not Swedish nationals. Oil company executives were recently indicted for war crimes in Sudan, after an investigation lasting 12 years, and an investigation has just been opened into the Syrian government in connection with a poison gas attack in 2013.

“This new refusal means this journalist is being completely abandoned by his country,” said Antoine Bernard, RSF’s director of advocacy and strategic litigation. “Sweden nonetheless has a duty to protect its citizens. We will not accept this contradictory decision, and we are now considering what our response will be.”

Among other courses of action, RSF intends to directly confront Sweden about its obligation to protect its citizens. RSF also calls on governments, and the European Union, in particular, to adopt targeted sanctions against the Eritrean leadership if they are able to do so.

During an appearance before the Swedish parliament in a public hearing on December 8th, RSF expressed its regrets about the decision by the prosecutor’s office. RSF also urged parliament itself to push for EU sanctions, to call for an investigation, and stressed the need for the Swedish foreign ministry to stop opposing an investigation.

After consulting the foreign ministry about the first complaint filed in 2014 with RSF’s help, the prosecutor's office accepted the ministry’s argument that opening an investigation would jeopardise the chances of obtaining Dawit Isaak’s release through diplomatic channels.

Five years later, in October 2020, after diplomatic efforts had clearly failed, RSF filed a new complaint, accusing the Eritrean president and several of his top ministers and advisers of crimes against humanity. This second complaint was also rejected by the prosecutor’s office for the same reasons. RSF then asked the prosecutor’s office to reconsider this decision. After this new request was rejected, RSF turned to the office of the prosecutor-general, which has just issued a final decision.

RSF will also contribute to the work of the Swedish parliamentary commission of enquiry that was tasked in January with evaluating the actions taken by the government with the aim of securing the release of Swedish citizens detained abroad, including Dawit Isaak. RSF had been calling for such a commission to be set up for several years.

Dawit Isaak has been detained in Eritrea since September 2001 without ever being brought to trial. Held incommunicado for 20 years in the most appalling conditions, he and colleagues arrested at the same time are now the world’s longest-held journalists.

Eritrea is at the very bottom of RSF's 2021 World Press Freedom Index, which ranks 180 countries, while Sweden is ranked third.