World Press Freedom Index 2010

Europe falls from its pedestal, no respite in the dictatorships

Africa

Five decades after independence, African journalists still seeking freedom

Horn still worst off, censorship hits Sudan and Rwanda, prison death mars Cameroon

With many African countries marking the 50th anniversary of their independence, 2010 should have been a year of celebration but the continent’s journalists were not invited to the party. The Horn of Africa continues to be the region with the least press freedom but there were disturbing reverses in the Great Lakes region and East Africa.

Eritrea (178th) is at the very bottom of the world ranking for the fourth year running. At least 30 journalists and four media contributors are held incommunicado in the most appalling conditions, without right to a trial and without any information emerging about their situation. Journalists employed by the state media – the only kind of media tolerated – have to choose between obeying the information ministry’s orders or trying to flee the country. The foreign media are not welcome.

In Somalia (161st), the media are not being spared by the civil war between the transitional government and Islamist militias, and journalists often fall victim to the violence. The two leading Islamist militias, Al-Shabaab and Hizb-Al-Islam, are gradually seizing control of independent radio stations and using them to broadcast their religious and political propaganda.

The temporary lifting of prior censorship on the print media in Sudan (172nd) was just a smokescreen. It has fallen 24 places and now has Africa’s second worst ranking, partly as a result of the closure of the opposition daily Rai-al-Shaab and the jailing of five members of its staff, but above all because of the return of state surveillance of the print media, which makes it impossible to cover key stories such as the future referendum on South Sudan’s independence.

Rwanda (169th), where President Paul Kagame was returned to power in a highly questionable election, has fallen 12 places and now has Africa’s third worst ranking. The six-month suspension of leading independent publications, the climate of terror surrounding the presidential election and Umuvugizi deputy editor Jean-Léonard Rugambage’s murder in Kigali were the reasons for this fall. Journalists are fleeing the country because of the repression, in an exodus almost on the scale of Somalia’s.

Surveillance of the press and a decline in the climate for journalists during the May elections account for Ethiopia’s continued bad ranking (139th). Violence against journalists, arbitrary police arrests and intelligence agency abuses explain why Nigeria (145th) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (148th) are still in the bottom third.

Uganda (96th) fell a relatively modest 10 places but the murders of two journalists in separate incidents in September and the recent increase in physical attacks and arrests of journalists are fuelling serious concerns about the climate for the media in the run-up to next year’s elections. Cameroon (129th) fell 20 places as a result of newspaper editor Bibi Ngota’s death in prison and the continuing detention of two other editors. Côte d’Ivoire (118th) also fell a few places due to the harassment of newspapers such as L’Expression and Le Nouveau Courrier d’Abidjan and the temporary ban on local retransmission of French TV station France 24 in February.

Gambia (125th) and Niger (104th) were neck and neck last year at a 137th and 139th thanks to the predatory behaviour of their respective presidents, Yahya Jammeh and Mamadou Tandja. But press freedom in Niger has improved markedly since Tandja’s overthrow in February, accounting for its 35-place jump, although the situation is still very uncertain. Uncertainty is also the dominant feature of another country in transition, Guinea (113th). It fell 13 places because of a massacre on 28 September 2009 but a new government that could show more respect for press freedom is still seen as a possibility.

After two difficult years, Kenya (70th) has recovered a respectable position. Chad (112th) is also leaving behind the fraught period in 2008 when a state of emergency was imposed, but the level of freedom allowed the press is still insufficient. Angola (104th) has an acceptable ranking although the situation has been soured by a Radio Despertar journalist’s still unsolved murder in September 2010.

After sharp falls in 2009, Gabon (107th) and Madagascar (116th) have recovered some of the lost ground thanks to a decline in tension. But Madagascar’s transitional authorities need to show more respect for the press by ceasing to jail journalists (such as those of Radio Fahazavana) and ceasing to close down news media. Zimbabwe (123rd) has again made some slow progress, as it did last year. The return of independent dailies is a step forward for public access to information but the situation is still very fragile.

Two more African countries have entered the ranks of the world’s top 50 nations in terms of respect for press freedom. They are Tanzania (41st), although certain stories such as albinism continue to be off-limits for the press, and Burkina Faso (49th), even if justice still has not been rendered in the case of Norbert Zongo, a journalist who was murdered 12 years ago.

The relative positions of the African countries in the top 50 have also changed. They are now led by Namibia (21st), which has recovered its former pre-eminent position, while Cape Verde (26th) has caught up with Ghana (26th) and Mali (26th). South Africa (38th) has fallen five places, in part because of attacks on journalists during the Football World Cup but above all because of the behaviour of senior members of the ruling African National Congress towards the press. ANC Youth League leader Julius Malema, for example, expelled BBC correspondent Jonah Fisher from a news conference on 8 April, calling him a “bastard” and “bloody agent.” And the government plans to create a media tribunal and to pass a bill restricting the disclosure of information. Both projects would endanger press freedom.

Americas

Noteworthy breakthroughs in Central America ; Brazil vaults back into the top of the Index

After Honduras in 2009, drained more than ever by the consequences of the coup d’état on the freedom to inform, the year’s most impressive changes concern three other Central American countries. Christian Poveda’s murder on 2 September 2009, at the beginning of the period considered, should logically have hurled El Salvador into the bottom of the Index. Yet the opposite occurred because of efforts undertaken and results obtained by Mauricio Funes’ government against impunity in this case. Even if the media (particularly those of the community) are not safe from threats, the absence of any aggression or serious acts of censorship are rocketing this reputedly dangerous country into an enviable position. A positive trend is also emerging in Guatemala, where results included no one killed, unlike in preceding years.

Panama has taken an opposite direction, in an atmosphere growing increasingly tense between the media and the authorities. Three serious episodes explain this sudden drop. First, the detention – at the end of June and for nineteen days – of retired journalist Carlos Nuñez, on grounds of a conviction for “defamation and “insult” which happened twelve years earlier and of which he had not even been aware. Next, the harsh treatments inflicted in his cell on a photographer arrested because of a harmless negative. Lastly, the threats, accompanied by an expulsion procedure, which were imposed on Spanish journalist Paco Gómez Nadal, a critical columnist and defender of indigenous rights. During this time, neighbouring Costa Rica was still holding its position among the highest-ranked Latin American countries. Further to the north, the United States (50 states of the union) and Canada still occupy the continent’s best positions, but they lag behind some twenty other countries. The initial results of the Obama administration in terms of access to information are disappointing.

Honduras brings up the rear in Central America, with a human track record comparable to that of Mexico, which is nonetheless slightly ahead of it, but followed, heading southward in the Index, by Colombia, where havoc caused by the country’s Administrative Department of Security (DAS) was accompanied by two murders of journalists (one of which involved a confirmed work-related motive). The situation is still tense in the Dominican Republic, where it is not healthy to be involved in corruption or drug trafficking, but it is becoming critical again in the Andean countries. Bolivia’s and Ecuador’s rankings have lost ground because of the violent acts, intimidations and blocked activities fostered by a pervasive climate of media-related political polarisation. The situation is affecting the state-owned, as well as privately owned, media. Peru has once again dropped some places because it still has not only a high incidence of assaults, but also of censorships ordered by high-ranking officials, and of abuses of process against the media. The same factors explain Venezuela’s new plunge, where the regime’s monopoly of the audiovisual terrestrial broadcast network and the excessive use of lengthy presidential speeches leaves little room for pluralism.

Cuba gained several places after the wave of dissident releases – notably the “Black Springtime” of March 2003 – which began in July 2010. So far, five journalists remain imprisoned in the continent’s only state which does not recognise any independent media. If the regime has made some concessions on behalf of its political prisoners in exchange for forced exile, it still has not made any with regard to public freedoms.

Persistent problems in the South

The other countries share some persistent problems – an over-concentration of media, economic disparities, local tensions, excessive number of legal proceedings, media coverage restrictions. Brazil can now be added to the countries with improved rankings already observed in the South Cone (Argentina, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay). The Latin American giant owes its better position to a decline in incidents of serious violence – which had previously been undermining certain regions – and to some pledges to fight against impunity in certain affairs. It also owes its improved ranking to favourable legislative changes in matters relating to access of information and editorial freedom, such as the reaffirmation of the right to caricaturise in an election period. Lastly, Brazil is one of the world’s most active Internet communities. The situation there would be better still if preventive censorship measures were not being imposed on certain media outlets.

In the area’s English-speaking nations, only Guyana experienced a significant reversal, due to the often strained relations between the media and the presidency, as well as to the government’s radio monopoly. It is somewhat outranked by the six islands of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), which entered the Index with the same rankings, right after Haiti, where the media are ensuring their survival by focusing on rebuilding after the 12 January 2010 earthquake.

Europe & ex-USSR

Central Asia, Turkey and the Ukraine cause concern, while the European model weakens

Already denounced in the 2009 edition of the World Press Freedom Index, the often liberticidal legislative activity of certain European Union Member States, and the new upsurge in anti-press proceedings brought by political leaders, are weakening the European freedom of expression model and, in so doing, are undermining its external policy and the universal impact of its values. Ireland is still punishing blasphemy with a EUR 25,000 fine. Romania now considers the media a threat to national security and plans to legally censor its activities. In Italy, where ten or so journalists still live under police protection, only an unprecedented national media mobilisation’s tenacity helped to defeat a bill aimed at prohibiting the publication of the content of telephone call intercepts, one of the main sources used in judicial and investigative journalism. Although the United Kingdom still benefits from a free and high-quality media, its defamation laws offer grounds for assembly-line trials brought by censors of every sort. Not only would this be counter-productive, but all such actions would complicate the mission of those who, outside of the EU, are trying to secure the decriminalisation of press offences.

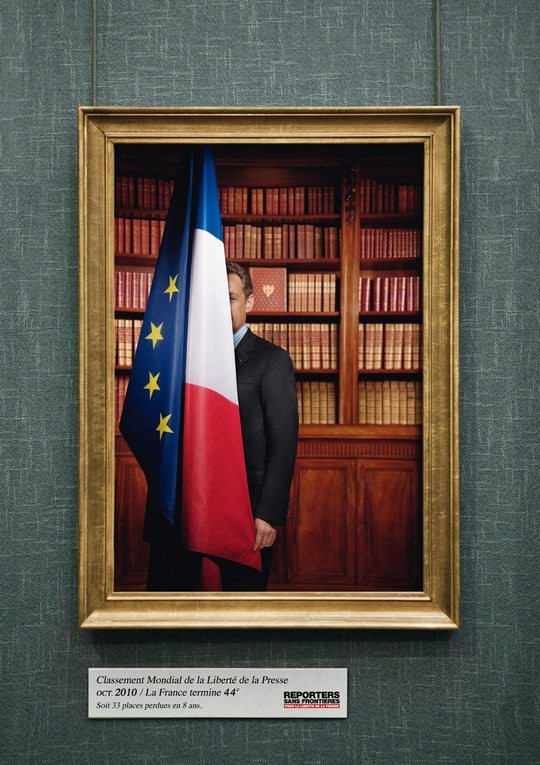

The heads of European governments, like their parliamentary colleagues, are gaining notoriety for their increasingly systematic use of proceedings against the news media and its journalists. The latter have to endure the insults which political leaders allow themselves to indulge in ever more frequently in their statements, following, in such matters, the deplorable example of press freedom predators, and overlooking the moral obligations inherent in their public office. In Slovenia, the former Prime Minister is thus competing with Silvio Berlusconi and Robert Fico by demanding no less than 1.5 million euros from a journalist who denounced irregularities tainting certain procurement contracts. In France, the presidential majority could not find words harsh enough to label journalists who inquired into the Woerth/Bettencourt affair. But the prize for political meddling goes to the Greek government which, in a manner not unlike most of the government censors, went so far as to request its German counterpart to apologise for the Greek economic crisis headline used by the magazine Stern.

Among the EU-27 countries whose rankings declined the most, Bulgaria continues its slide and has ended up, along with Greece, in 70th place – the worst position held by EU member countries. France (44th) and Italy (49th), still dealing with some major interference in media activity by their political leaders, confirmed their status as the “dunces” of the EU’s founding countries. Although we may welcome with cautious relief the ebbing ETA attacks against the media in Spain (39th), we cannot help but be concerned by the court verdict of 21 months in prison and the prohibition to exercise their profession brought against Daniel Anido, director of the private radio station Cadena SER, and Rodolfo Irago, the news director of the same radio network. In Denmark (11th) as well as Sweden (1st), press freedom is faring well, but murder attempts against cartoonists Kurt Westergaard and Lars Vilks are opening a door to self-censorship, which until now had been negligible, in a climate of rising extremism and nationalism. Slovakia (35th), which is just emerging from former Prime Minister Robert Fico’s tumultuous era, now merits watching, while among the Baltic States, Latvia (30th) is experiencing an odd return to violence and censorship in an electoral period. Although weakened, the European Union remains one of the rare areas in which the media can exist under acceptable conditions. Naturally, constant vigilance is needed to ensure that this weakening can be freely fought. The European Parliament, though legitimately very active internationally in such issues, has shown the full limits of its exercise of power in refusing, by one vote, in plenary session, to address the subject of press freedom in Italy.

The Balkan Peninsula is still a concern and has recorded major changes. Montenegro (-27), Macedonia (-34), Serbia (-23) and Kosovo (-17) constitute the most substantial losses. Although the legislative reforms required for accession to the EU have been adopted in most Balkan countries, their implementation is still in the embryonic – if not non-existent – stage. Control of the public and private media by the calculated use of institutional advertising budgets and the collusion between political and judicial circles is making the work of journalists increasingly difficult. In a precarious situation, caught in a vice between the violence of ultranationalist groups and authorities who have not yet rid themselves of old reflexes from the Communist era, an increasing portion of journalists are settling for a calculated self-censorship or a mercenary journalism which pays better, but gradually ruins the profession’s credibility. Blighted by mafioso activities which, every year, strengthen their financial stranglehold on the media sector, independent publications are waging an ongoing battle which deserves more sustained attention from European neighbours.

At Europe’s doors, Turkey and Ukraine are experiencing historically low rankings, the former (138th) being separated from Russia’s position (140th) only by Ethiopia (139th). These declines can be explained, as far as Turkey is concerned, by the frenzied proliferation of lawsuits, incarcerations, and court sentencing targeting journalists. Among them, there are many media outlets and professionals which are either Kurd or are covering the Kurd issue. Ukraine is paying the price of the multiple press freedom violations which have broadsided the country since February 2010 and Viktor Yanukovych’s election as Head of State. These violations initially met with indifference by the local authorities. Worse still, censorship has signalled its return, particularly in the audiovisual sector, and serious conflicts of interest are menacing Ukraine’s media pluralism.

Russia now occupies a position (140th) more like it had in previous years, with the exception of 2009, which was marred by the murder of several journalists and human rights activists. Nonetheless, the country has recorded no improvement. The system remains as tightly controlled as ever, and impunity reigns unchallenged in cases of violence against journalists.

Central Asia’s prospects are dismal. In addition to Turkmenistan, which – in the 176th place – is still one of the worst governments in the world in terms of freedom (only the state-owned media is tolerated there and even that is often “purged”), Kazakhstan (162nd) and Kyrgyzstan (159th) are ranked dangerously close to Uzbekistan, holding steady in the 163rd position. Almaty has gained notoriety through repeated attacks on the rights of the media and journalists in the very year in which he presides over the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), when the country is bound to be subjected to particularly close scrutiny. Despite repeated calls for remedying problems of all kinds which are hampering media activity, authorities have not deemed it necessary to do so, nor to release Ramazan Eserguepov, detained in prison for political reasons. Kazakhstan’s neighbouring country, Kyrgyzstan joined this descent into the depths of the Index, to the discredit of April’s change of power and June’s inter-ethnic conflicts. As for Uzbekistan, the core of independent journalists who refuse to give up is now in the judicial authorities’ line of fire. Documentary film-makers, like trusted journalists, have also been victims of the regime’s paranoia. All of these developments have only been met with indifference on the part of the European States, too concerned about energy security to protest scandalous practices which violate every international commitment made by Central Asian governments.

Lastly, the situation is dreary and stable in Belarus, torn between two allegiances – one to Moscow and the other to the EU – and caught up in a delicate balancing act between these two powers. The regime makes no concession to civil society and continues, as the December presidential elections approach, to put pressure on the country’s few remaining independent media outlets.

Asia

Asian Communist regimes still hold the lowest rankings

Asia’s four Communist regimes, North Korea (177th place), China (171st), Vietnam (165thj) Laos (168th), are among the fifteen lowest-ranked countries of the 2010 World Press Freedom Index. Ranked just one place behind Eritrea, hellish totalitarian North Korea has shown no improvement. To the contrary: in a succession framework set up by Kim Jong-il in favour of his son, crackdowns have become even harsher. China, despite its dynamic media and Internet, remains in a low position because of non-stop censorship and repression, notably in Tibet and Xinjiang. In Laos, it is not so much repression which plagues this country of Southeast Asia as its single party’s political control over the whole media. On the other hand, Vietnam’s Communist Party – soon to hold its own Congress – and its open season against freedom of speech is responsible for its worse than mediocre ranking.

Among the last thirty countries of Reporters Without Borders’ Index are ten Asian nations, notably Burma, where the military junta have decided that the prior censorship system will be maintained despite the upcoming general elections in November.

India’s and Thailand’s rankings drop due to a breakout of serious violence

Political violence has produced some very troubling tumbles in the rankings. Thailand (153rd) – where two journalists were killed and some fifteen wounded while covering the army crackdown on the “red shirts” movement in Bangkok – lost 23 places, while India slipped to 122nd place (-17) mainly due to extreme violence in Kashmir. The Philippines lost 34 places following the massacre of over thirty reporters by partisans of one of Mindanao Island’s governors. Despite a few murderers of journalists being brought to trial, impunity still reigns in the Philippines. Also in Southeast Asia, Indonesia (117th) cannot seem to pass under the symbolic bar separating the top 100 countries from the rest, despite remarkable media growth. Two journalists were killed there and several others received death threats, mainly for their reports on the environment. Malaysia (141st), Singapore (136th) and East Timor (93rd) are down this year. In short, repression has not diminished in ASEAN countries, despite the recent adoption of a human rights charter. In Afghanistan (147th) and in Pakistan (151st), Islamist groups bear much of the responsibility for their country’s pitifully low ranking. Suicide bombings and abductions make working as a journalist an increasingly dangerous occupation in this area of South Asia. And the State has not slackened its arrests of investigative journalists, which sometimes more closely resemble kidnappings.

Democratic Asian countries gain ground

Asia-Pacific country rankings can be impressive. New Zealand is one of the ten top winners and Japan (11th), Australia (18th) and Hong Kong (34th) occupy favourable positions. Two other Asian democracies, Taiwan and South Korea, rose 11 and 27 places respectively, after noteworthy falls in the 2009 Index. Although some problems persist, such as the issue of the state-owned media’s editorial independence, arrests and violence have ceased. Some developing countries have managed to make solid gains, particularly Mongolia (76th) and the Maldives (52nd). As a rule, the authorities have been respectful of press freedoms, exemplified by their decriminalisation of press offences in the Maldives. An occasional ranking in this Index can be deceptive. Fiji (149th), for example, rose three places, even though the government has passed a new liberticidal press law. The year 2009 had been so tragic, with soldiers invading news staff offices, that the year 2010 could only seem to be somewhat more tranquil. Sri Lanka (158th) jumped four places: less violence was noted there, yet the media’s ability to challenge the authorities has tended to weaken with the exile of dozens of journalists. In this Index based upon violations of press freedoms, Asia, has earned a low ranking for yet another year. Even when a country’s press enjoys freedom, too often it also has to endures violence from non-governmental actors. When the press lives under the control of an authoritarian regime, it is obliged to censor and to self-censor. Chinese intellectual Liu Xiaobo was sentenced to eleven years behind bars for denouncing this situation – a struggle which was rewarded by the Nobel Peace Prize – bringing new hope to the Asia-Pacific area.

Middle East & North Africa

Confirmed downward trends

Morocco’s drop (-8 places) reflects the authorities’ tension over issues relating to press freedom, evident since early 2009. The sentencing of a journalist to one year in prison without possibility of parole (he will serve eight months), the arbitrary closing down of a newspaper, the financial ruin of another newspaper, orchestrated by the authorities, etc. – all practices which explain Morocco’s fall in the Index rankings.

Tunisia’s score was (-10), falling in position from 154th to 164rd (Tunisia had already lost 9 places between 2008 and 2009). The country is continuing to drop into the Index’s lower rankings because of its policy of systematic repression enforced by government leaders in Tunis against any person who expresses an idea contrary to that of the regime. The passage of the Amendment to Article 61B of the Penal Code is especially troubling in that it tends to criminalise any contact with foreign organisations which might ultimately harm Tunisia’s economic interests.

There is an identical situation in Syria (-8) and Yemen (-3), where press freedom is fast shrinking away. Arbitrary detentions are still routine, as is the use of torture.

For its part, Iran held its position at the bottom of the Index. The crackdown on journalists and netizens which occurred just after the disputed re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in June 2009 only strengthened in 2010.

Only a relative improvement in some countries

At first glance, the 2010 index’s higher score as compared to that of 2009 seems to translate into gains. However, it is important to emphasise how troubling the situation had been in 2009. In that regard, 2010 actually spells out a return to the pre-existing equilibrium, with no sign of significant progress in these countries.

Such is the case of Israel (extra-territorial) which “won” 18 places in the index, passing from the 150th to the 132nd place. The year 2010 was not exempt from press freedom violations on the part of the Israeli Army, as evidenced by the cases of foreign journalists arrested on the flotilla in May 2010, or the Palestinian journalists who are regularly targeted by Tsahal soldiers’ bullets. Or the skirmish in South Lebanon last August, during which a Lebanese journalist was killed. However, 2010 is incommensurate with 2009, in the early days of which "Operation Cast Lead" took place: six journalists died, two of them while doing their jobs, and at least three buildings sheltering media professionals were targeted by gunfire.

The Palestinian Territories had similar results, rising 11 places in the 2010 index (now 150th instead of 161st). The violations committed in the year just ended are simply “less serious” than in 2009, even if the journalists and media professionals are still paying the price for the open hostility between the Hamas and the Fatah.

In Algeria, the number of legal proceedings instituted against journalists has noticeably declined, which explains its gain of 8 places in the Index. Between 2008 and 2009, the country had dropped 20 places due to the increased number of legal proceedings.

Iraq climbed 15 places (now 130th), because safety conditions for journalists improved substantially in the country, despite the fact that three had died between 1 September 2009 and 31 August 2010 – two of whom were murdered. Since then, three deaths have occurred in less than one month. The withdrawal of U.S. combat troops from Iraq at the end of August necessarily marks the start of a new era. The security of citizens, and particularly of journalists, should not be made to suffer for it.

Drops in Persian Gulf

Bahraini’s ranking in the Index dropped from 119th to 144th place, which can be explained by the growing number of imprisonments and trials, notably against bloggers and netizens.

Another noteworthy drop was that of Kuwait, which fell 27 places, from the 60th to the 87th position, mainly because of the Kuwaiti authorities’ harsh treatment of lawyer and blogger Mohammed Abdel Qader Al-Jassem, who has been jailed twice following accusations lodged by prominent figures with close ties to the regime. This contradicts the authorities stated desire to project an image of being the leading democracy of the Persian Gulf.