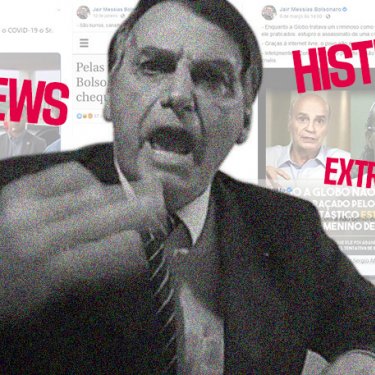

Brazil quarterly analysis. President Bolsonaro’s systematic attempts to reduce the media to silence

In the first of a new series of quarterly assessments of press freedom violations in Brazil in 2020, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) examines President Jair Bolsonaro’s strategy for smearing and undermining the journalists and media outlets that annoy him.

Ever since taking office in January 2019, President Bolsonaro has insulted, denigrated, stigmatized and humiliated journalists whenever they publish or broadcast something contrary to his or his administration’s interests. And in this, he has been helped by members of his family, some of his ministers and an army of social media supporters.

Although they take many forms, these systematic attacks on the media obey a clear and increasingly well-oiled strategy – to encourage a lasting mistrust of the targeted journalists, destroy their credibility, and gradually construct a common enemy. They also have a common goal – to control the public debate and avoid having to address the substance of questions. In the first three months of the year, RSF has registered no fewer than 32 attacks by President Bolsonaro against journalist and the media in general, an average of one every three days.

Coronavirus crisis proves revealing

“The public will realize fairly quickly that it has been deceived by the media,” President Bolsonaro said during an interview for TV Record on 22 March, the day that Brazil officially reported 1,800 coronavirus cases and 34 deaths. During a formal address on national TV two days later, he called Covid-19 “a little flu” and added: “Many of the media spread a feeling of fear by exploiting the many victims in Italy, a country with a lot of elderly people and whose climate is totally different from ours (...) a perfect scenario, transmitted by the media for hysteria to take over our country.”

His own health minister, Enrique Mandetta, followed suit in an interview on 28 March, describing the media’s reporting as "sordid" and "toxic" and urging the Brazilians to "turn off their TV sets for a while.”

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to spread in Brazil, with 28.320 cases and 1.736 deaths when this analysis was published, Bolsonaro continues to deny reality and to call for the lockdown to be lifted. After he posted videos on his official Twitter and Instagram accounts that showed him walking through the streets of Brasilia and mingling with the public, in effect questioning the point of the lockdown and contradicting his own government’s instructions and World Health Organization advice, Twitter and Instagram censored his accounts on 29 and 30 March on the grounds of irresponsibility, in a highly unusual sanction on a country’s leader.

President Bolsonaro’s Twitter account censored by Twitter on 29 March

Public humiliation and online “lynching”

Although now highlighted by the Covid-19 crisis, the attacks on journalists have been growing since the start of the presidential campaign in late 2018. But they have taken a new turn since the start of 2020, with carefully staged acts designed to humiliate journalists publicly.

A surreal scene was enacted at the start of a press conference outside the Alvorada Palace, the president’s official residence in Brasilia, on 3 March and was broadcast live on the president’s social media accounts. Bolsonaro arrived in his official car together with a comedian who impersonates him and he asked the comedian to distribute bananas to the journalists (which in Brazil symbolizes giving them the finger). Later during the press conference, when he was asked about Brazil’s poor economic performance, Bolsonaro laughingly asked his impersonator to answer in his stead.

President Bolsonaro and his impersonator make fun of journalists in Brasilia on 3 March (Photocredits: Dida Sampaio / Estadão Conteúdo).

He humiliated the same journalists outside the Alvorada Palace on 26 March. “Look, people of Brazil,” he said, pointing at the journalists. “These people say I’m wrong and that you should stay at home.” Turning towards the journalists, he added” “What are you doing here? Aren’t you afraid of the coronavirus? Go home!”

Such attacks are widely echoed on social media, where Bolsonaro is very active and does not hesitate to spread fake news (about the uses of chloroquine, for example). According to the annual report by the Brazilian Association of Radio and TV Broadcasters (ABERT), there were four million online attacks on professional media outlets and journalists in 2019, or seven attacks a minute. The report said that, of 39.2 million posts containing the words “press,” “journalist,” “journalism” “or “media,” 10% were direct attacks, above all by conservative, pro-Bolsonaro politicians and news sites. The report said: “Journalists who publish content critical of the government have become the targets of systematic online attacks, promoted by bots and government supporters whose aim is to undermine the media’s credibility.” Women are favourite targets.

Women journalists – leading victims

Patrícia Campos Mello, a veteran journalist with the Folha de São Paulo daily newspaper and former war reporter, is one of the favourite targets of what some call the “Bolsonaro system.” In October 2018, she reported that businessmen were illegally funding a WhatsApp disinformation campaign designed to get Brazilians to vote for Bolsonaro in the presidential election, the second round of which was held later that month. Her story triggered a ferocious online campaign of insults and threats against her by Bolsonaro supporters.

In the course of an investigation into her revelations, an Anti-Fake News Parliamentary Commission heard testimony on 11 February 2020 from Hans Nascimento, the employee of one of the digital marketing companies alleged to have helped send millions of fake WhatsApp messages. Nascimento testified to the commission that Mello tried to extract information from him in exchange for sexual favours. Although Mello and Folha de São Paulo issued immediate denials, Nascimento’s claim triggered a torrent of sickening and salacious comments, including by President Bolsonaro himself, and were repeated by several parliamentarians, including the president’s son, Eduardo Bolsonaro. Speaking in the chamber of deputies, he said: “I do not doubt that Ms. Patrícia Campos Mello may have offered sexual favours, as Mr. Hans said, in exchange for information to try to harm President Jair Bolsonaro’s campaign.” Widely relayed on social media, these insinuations triggered new wave of sexist and misogynous insults and threats against her.

Vera Magalhães, another well-known woman journalist, who hosts TV Cultura’s famous current affairs programme Roda Viva, was also the target of many attacks by the president and his sons and allies in the first quarter of 2020, above all because she demonstrated on Twitter that the president had lied and had privately urged supporters to stage protests against the Brazilian supreme court and national congress, which resulted in calls for him to be impeached for “criminal responsibility.”

The president’s sons are among the most aggressive of those who attack journalists on social media. According to RSF’s tally, the parliamentarian Eduardo Bolsonaro was responsible for at least 30 attacks on the media in March alone. Joice Hasselmann, a parliamentarian who used to be a presidential ally, revealed the existence of a “hate cabinet” that orchestrates large-scale attacks against journalists.

Consisting of very close presidential advisers and coordinated by his second son, Carlos Bolsonaro, this group has above all trained its sights on Mello and two other journalists, Constança Rezende and Glenn Greenwald, who have repeatedly been the target of social media hate campaigns because of their revelations about the Brazilian government. This “hate cabinet” is on the list of Digital Predators of Press Freedom that RSF published on 10 March.

The cases of Mello and Magalhães are typical of the crude machismo that characterizes the behaviour of the president and his supporters. In a report requested by the UN and published on 13 March, the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalists (ABRAJI) provided a detailed description of the environment for Brazilian journalists, which includes misogynous attacks, smears and exposure of personal details. According to the report, there were at least 20 “gender attacks” against women journalists in January and February, 16 of them by state officials.

State involvement – judicial and economic harassment

As well as his supporters, the president has also pressganged state institutions into his fight against critical and independent media outlets.

The best example is the persecution of Glenn Greenwald, a Rio de Janeiro-based US journalist who founded The Intercept Brasil news site. In June 2019, The Intercept Brasil began publishing a series of reports based on information from an anonymous source exposing highly compromising collusion between the judge and prosecutors in a huge anti-corruption investigation known as Operation Car Wash. They triggered a massive wave of attacks on Greenwald, his family and his colleagues and, in July 2019, President Bolsonaro said Greenwald “could be imprisoned” without specifying any grounds. Although the federal police concluded that Greenwald had not broken any law and the supreme court reached the same conclusion, citing the constitutional right of journalists to protect their sources, a federal prosecutor nonetheless charged Greenwald on 21 January with having “directly assisted, encouraged and guided” the hackers who had supposedly provided him with the information. This absurd and unjustified charge has all the hallmarks of a political reprisal against Greenwald and his colleagues.

Such judicial harassment is very common in Brazil and is usually accompanied by financial pressure aimed at strangling the troublesome media outlets economically. President Bolsonaro and his staff have publicly and repeatedly called for boycotts of brands advertised in the Folha de Sao Paulo newspaper – which the president has banned from state distribution points – and have urged commercial advertisers not to place ads in newspapers and magazines, such as Folha de São Paulo, Época and Globo, that are critical of the government. At the same time, the president has urged advertisers to give preference to media “aligned with the government,” confirming his limited understanding of media pluralism.

The presidential communications department, known by the acronym Secom, has been subject to scrutiny since the start of the year by the Federal Accounting Court (TCU) for failing to respect the criteria of transparency and fairness in its allocation of state advertising, for which it is responsible. Record and SBT, media groups owned by Bolsonaro buddies Edir Macedo and Silvio Santos, have earned much more from state advertising than the Globo group, which is much bigger in audience terms but is in permanent conflict with Bolsonaro.

RSF and a coalition of partner organizations managed to get the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to hold a hearing on these systematic and institutionalized press freedom violations in the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince, on 6 March. It was the first time that the IACHR, an offshoot of the Organization of American States, had agreed to hold a public hearing on the threats to freedom of expression in Brazil and it constituted a very significant recognition by the OAS of the dramatic decline in the situation since Bolsonaro became president.

Brazil is ranked 105th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2019 World Press Freedom Index.